Under the radar: Florida lawmakers last year banned local ‘fair scheduling’ laws — here's what that means

It was one of several provisions in that broad bill banning local governments from adopting local laws to protect workers from extreme heat on the job.

Caring Class Revolt is a 100% reader-supported publication. And full disclosure, it’s a side project of mine that I work on outside of my full-time job as a local news reporter. I launched this Substack because I care about documenting news affecting Florida’s labor movement that otherwise goes under- or unreported. If you appreciate posts like this, please consider becoming a free or paid subscriber and/or sharing this publication with others.

Last year, Florida’s Republican-controlled state Legislature muscled through a sweeping anti-worker bill (H.B. 433) that prohibits local governments from enacting local laws that would help protect workers from extreme heat on the job.

Next year, the new law will also bar local governments from maintaining or enacting so-called ‘living wage’ laws, which require government contractors in places like Tampa, Miami-Dade and Broward Counties to pay their employees a wage higher than Florida’s current minimum wage — which, by the time that takes effect, will be $15 an hour.

But one part of that industry-backed law received less coverage, or attention, than the rest — maybe because it was slipped in last-minute.

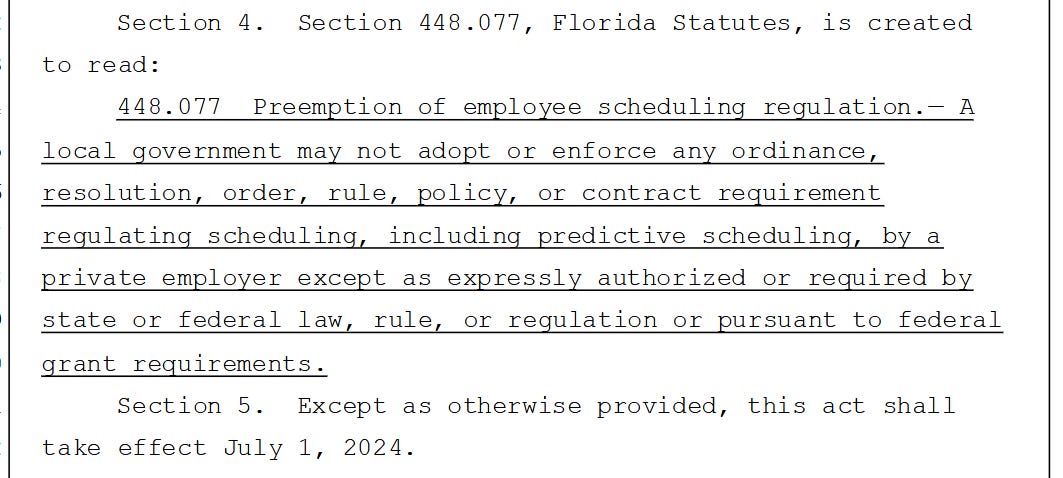

While Florida lawmakers, at the urging of the business lobby, initially sought to preempt to the state any local mandate affecting “terms and conditions of employment” through H.B. 433 — something that some critics worried could affect anti-discrimination policies, for example — Florida Republicans eventually settled on preempting local minimum wage laws, as well as local “predictive scheduling” mandates.

If this type of law sounds unfamiliar, that might be because no such thing actually exists in Florida. So, what does it mean?

Predictive scheduling, sometimes referred to as “fair scheduling” or “fair workweek” laws, are a type of pro-worker policy that require employers to provide workers with their schedules in advance — usually with two weeks’ notice.

For many hourly workers, including those in the service, hospitality, and retail industries, this is basically unheard of in most parts of the country.

According to HR Dive, Oregon is the only state in the U.S. to have a statewide fair scheduling law on the books, as of last May. At least 11 states in the country, Florida included, preempt them.

There has been greater success in getting some of these laws through on the local level, however, at least in states that don’t explicitly prohibit them. At least 10 U.S. cities across five additional states have adopted their own fair scheduling mandates, including Chicago, Seattle, New York City, Philadelphia, and various municipalities in California.

In Los Angeles, for example — which enacted its own fair workweek law last year — certain employers are now required to give employees their schedules at least two weeks in advance and pay them for any last-minute schedule changes. Employers are also required to space out workers’ shifts by at least 10 hours, according to the LA Times.

The local ordinance in L.A. is limited, applying specifically to retail employers with more than 300 employees globally. Local laws in other parts of the country are similarly limited, or in some cases, apply more broadly to other industries as well.

Chicago’s fair workweek law, for instance, affects businesses with at least 100 employees, nonprofits with more than 250 employees, and restaurants with at least 30 locations and 250 employees, according to HR Dive. Covered employees include workers who earn up to $61,149.35 annually, or no more than $31.85 per hour.

The idea behind predictive scheduling is pretty simple: It’s supposed to provide workers with greater stability, flexibility, and a better understanding of what their schedule is going to look like.

Essentially, this gives people the ability to coordinate other aspects of their lives — for example, securing childcare or a babysitter, so a kid isn’t left alone at home while Mom or Dad is at work; scheduling a medical appointment; or transportation to and from the job.

Maybe a working mom just wants to know if she’ll be able to attend her daughter’s piano recital without worrying that her boss is going to call her in last-minute. Or, she needs an idea of when she can schedule an appointment with a doctor or other medical provider.

Unpredictable scheduling is the norm for food service and retail industries in particular — where workers are less likely to have union representation and the ability to collectively advocate for better scheduling practices.

In Florida, only about 3% of private sector workers are represented by a union, compared to about 8% of the private sector workforce in Oregon. In addition to advocating for improved scheduling practices during contract negotiations, a union can also help back you up if your boss fails to comply with an applicable fair scheduling law.

Take, for instance, unionized Starbucks workers in Philadelphia and Chicago who filed complaints against the Seattle-based coffee giant last February for alleged violations of local fair scheduling ordinances in their communities and retaliation for speaking up about it.

“What I hope happens from this is that, together, we make Starbucks a good place to work again,” one worker told the Philadelphia Inquirer.

According to the Inquirer, some employers in Philly have been forced to pay tens of thousands of dollars in damages for violations of the local fair scheduling ordinance since its adoption in 2020, including major retailers like Target.

The Economic Policy Institute, a pro-labor think tank, notes that unpredictable, irregular work schedules can create a number of challenges for working people. It can make it difficult for workers to explore other job opportunities, or to hold down a second job. It can also make it trickier to manage household budgets, and may cause conflicts at home.

Backers of local fair scheduling laws often include worker advocacy groups, labor unions like the Service Employees International Union (SEIU), and other worker-led movements, according to the blog OnLabor.

“Philadelphia approved its legislation only after workers and advocates executed a year-long campaign for predictable scheduling,” wrote OnLabor contributor and legal engineer Alex Blutman. “Seattle’s scheduling law followed a national movement spearheaded by Starbucks baristas, in conjunction with Working Washington, featuring nationwide rallies and petitions signed by tens of thousands of workers. Starbucks employees, joined by workers from McDonald’s, Domino’s, REI, Target, and others, helped convince the Seattle City Council to enact its Secure Scheduling law, which passed in 2016 with support from local chapters of the United Food and Commercial Workers Union and the Service Employees International Union, as well as the King County Labor Council.”

Unsurprisingly, these proposals often receive push-back from business groups like Chambers of Commerce, which argue such mandates are “unrealistic” and bad for workers.

In Colorado, a coalition of business groups reportedly managed to kill a statewide fair scheduling proposal in 2023, with restaurant industry leaders claiming that their employees “are attracted” to job opportunities with unpredictable scheduling because it allows them to “swap shifts ranging from attending parent-teacher conferences to snagging last-minute concert tickets.”

As I mentioned earlier, there are no local governments in Florida that have adopted predictive scheduling laws, to my knowledge, and I’m not aware of any recent efforts to do so either.

But we do know that the Florida Chamber of Commerce, and other industry groups like the Associated Industries of Florida — described as the “Voice of Florida Business” — lobbied hard to get this latest mega-preemption bill (H.B. 433) over the finish line.

Jason Garcia, investigative reporter and publisher of Seeking Rents, first uncovered through public records last year that the Chamber was behind at least some of language in the bill — namely, the attempt to preempt all “terms and conditions” of employment to the state.

Garcia reported then that the real aim of the language was fair scheduling laws in particular. The Foundation for Government Accountability, a billionaire-backed think tank that also drafted a bill to weaken child labor law in Florida last year also appeared to have been involved in bill drafting.

H.B. 433 was ultimately amended multiple times prior to its eventual passage on the final day of the 2024 legislative session, where it was largely passed along party lines, with Florida Republicans (and, of course, some of their most generous campaign contributors) in favor.

A political action committee (PAC) affiliated with then-Florida House Speaker Paul Renner, for instance, received a $50,000 check from the Chamber just one day before the 2024 legislative session was scheduled to begin last January.

The same PAC received a $25,000 check from the Associated Industries of Florida — a major donor to Republican leaders and, randomly, a member of an anti-Medicare for All dark money group — just a couple of weeks before that.

From what I can tell from communications I obtained through a public records request, the push to get H.B. 433 past the finish line last year with as many preemptive provisions as possible, however, was truly a group effort.

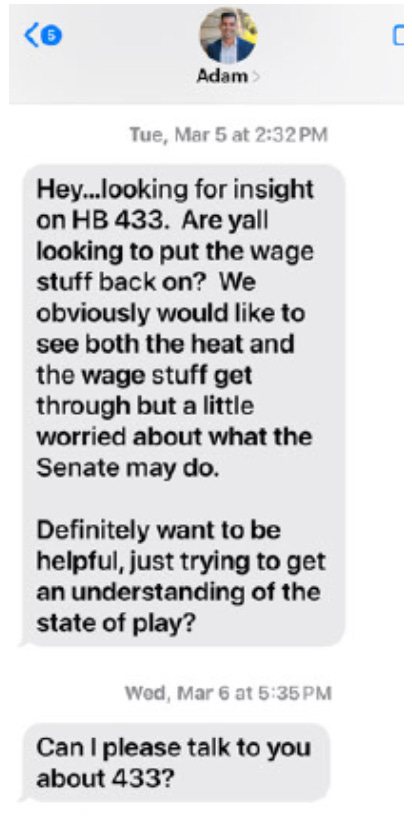

Some industry groups seemed more invested in securing the ban on local workplace heat protection laws, while others — including AIF — appeared to be more interested in the “wage stuff,” as one lobbyist for the group put it.

“We obviously would like to see both the heat and the wage stuff get through but a little worried about what the Senate might do,” one AIF lobbyist wrote, in a text to Renner’s chief of staff Allison Carter.

The lobbyist was referring to an amendment made to the Senate version of the bill that cut some of the broader language, focusing exclusively on prohibiting the workplace heat protection laws.

Unsurprisingly, the bill in all of its forms received fierce backlash from labor unions, as well as advocacy groups such as Equality Florida, the Southern Poverty Law Center, the Farmworkers Association of Florida, and the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU).

It’s important to note: No city or county in Florida even had any sort of workplace heat protection ordinance in place prior to H.B. 433’s passage. The first of its kind in Florida, driven by a movement of farm and agricultural workers, had been in the works in Miami-Dade County, where workers have faced record-breaking heat in recent years.

Business lobbyists managed to water it down, and convinced county leaders in November 2023 to delay a final vote of approval on the local ordinance. Florida’s H.B. 433, barring such ordinances statewide, was filed by Republican Florida Rep. Tiffany Esposito — the president of a regional Chamber of Commerce in South Florida — less than a week later.

Yet, the idea that the state would forbid local governments from trying to protect workers in their own communities from potentially deadly heat was just too cruel for many to fathom. It faced a tough crowd, even in Florida’s business-friendly state legislature.

So, as the end of the state legislative session neared, and the contentious bill — one of the most controversial last session — still hadn’t passed, lobbyists became more desperate in their pleas.

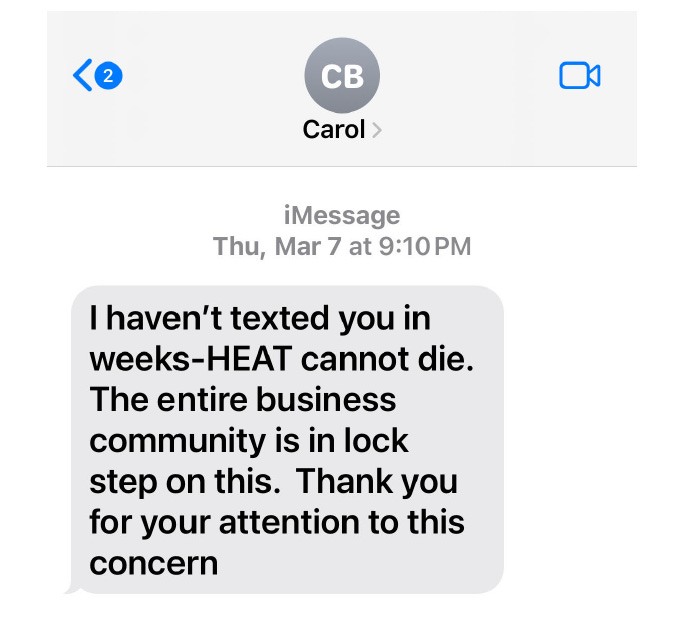

“I haven’t texted you in weeks–HEAT cannot die,” wrote a lobbyist for the Associated Builders and Contractors, in a late-night text message to Carter the day before the final day of session.

“The entire business community is in lock step on this,” the lobbyist added. “Thank you for your attention to this concern”.

The ban on local predictive scheduling laws was added to H.B. 433 on the final day of session, as Republican leaders rushed it through.

While that vague, exceptionally broad “terms and conditions” of employment language in the bill was ultimately cut, the bill nonetheless managed to prohibit local governments from requiring employers to adopt any sort of heat protection rules and prohibited local fair scheduling laws.

Effective Sept. 30, 2026, it will also prevent local governments from setting or maintaining minimum wages above the state’s wage floor for employers they enter into contracts with — that is, government contractors that receive taxpayer money for publicly-funded projects.

But it wasn’t the only controversial labor law last year to secure approval last year.

Florida’s House Bill 705, another priority of the business community that largely fell under the radar last session, preempts local prevailing wage mandates — essentially, local laws that can, in part, require government contractors on certain publicly-funded projects to pay their laborers industry-competitive wages.

Florida House Bill 49, weakening child labor protections for 16- and 17-year-olds, also passed the final day of the 2024 session, with just a couple of Republicans crossing party lines to join Democrats in opposition.

The Florida Restaurant & Lodging Association, a state affiliate of the National Restaurant Association, was one of the bill’s most vocal cheerleaders, representing more than 10,000 restaurateurs and hoteliers statewide, from Disney, to Universal Orlando, Benihana, DoubleTree and Hilton hotels.

In 2020, the group led an unsuccessful effort to defeat Florida’s $15 minimum wage ballot initiative, which ended up passing that year with roughly 61% of support.

The initiative, gradually raising Florida’s minimum wage each year until it reaches $15 per hour next September, received more votes of support that November than either presidential candidate in Florida, including Donald Trump.