Latest Florida bill targeting unions came from Gov. DeSantis’s office, records show

The proposal is dead for this year, but could have posed a critical threat to public sector unions that are still reeling from an anti-union law approved in 2023.

Caring Class Revolt is a 100% reader-supported publication. And full disclosure, it’s a side project of mine that I work on outside of my full-time job as a local news reporter. I launched this Substack because I care about documenting news affecting Florida’s labor movement that otherwise goes under- or unreported. If you appreciate posts like this, please consider becoming a free or paid subscriber and/or sharing this publication with others.

A controversial proposal filed by Republican state lawmakers this year that sought to make it harder for public employees in Florida to form a union or keep their existing union alive appears to have come from the governor’s office, according to records I obtained from the Florida Senate.

Although the proposal (HB 1387) died earlier this month, following the conclusion of Florida’s 60-day legislative session (sort of), the measure posed a critical threat to the state’s public sector unions — yet, notably saw support behind the scenes from the state agency that regulates them.

An early version of the legislation I obtained through a public records request contains metadata showing the original author of the proposal was Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis’ policy chief, Hannah DuShane. DeSantis has been in communication with several anti-union groups in recent years, and has taken aim at unions that have publicly opposed his policy agenda.

The proposal from the governor’s office was officially filed and sponsored by Rep. Jenna Mulicka-Persons and Sen. Blaise Ingoglia, both Republicans. It sought to, in part, make it harder for public employees to form unions by requiring that more than 50% of workers in a bargaining unit vote in favor of unionization for the union to prevail, rather than just a majority of those workers who vote.

Similar election rules, notably, are not recognized for private sector union elections conducted by the federal National Labor Relations Board, nor for politicians (like DeSantis and his allies) seeking election to public office.

The proposal bears a resemblance to a model policy prioritized this year by the American Legislative Exchange Council, a corporate-funded “bill mill” that feeds model policy templates to lawmakers in state legislatures across the country.

It also closely resembles draft legislation that the Freedom Foundation, an anti-union think tank, emailed to Republican Florida Sen. Blaise Ingoglia ahead of last year’s legislative session. The libertarian group, headquartered out-of-state, describes itself as a “battle tank” battering “the entrenched power of left-wing government union bosses who represent a permanent lobby for bigger government, higher taxes, and radical social agendas.”

The group last year unsuccessfully attempted to dismantle Florida’s largest local teachers union in Miami-Dade County, and has celebrated the passage of anti-union policies elsewhere, including a new law in Utah gutting public sector collective bargaining rights that labor advocates are now seeking to repeal through the ballot.

As I’ve pointed out before, the bill filed in Florida this year was sweeping and sought to do some rather petty things, in addition to changing election rules. It sought to, for instance, increase fines for strikes by government employees from $20,000 to $120,000 per day — an idea first pitched by the billionaire-funded Freedom Foundation.

Another idea drafted by governor’s office, but dropped before the bill was actually filed, would have increased the filing fee for unions to annually renew their registration with the state. As I reported last year, that idea also came from the Freedom Foundation, an affiliate of the conservative State Policy Network.

“The maximum fee is currently set at $15 and has not been adjusted for inflation since the collective bargaining law was passed in 1975,” Christian Cámara, a contracted lobbyist for the Freedom Foundation, explained in an email to Sen. Ignoglia and Rep. Dean Black in November 2023 (obtained through a public records request). Both lawmakers sponsored anti-union legislation passed and approved earlier that year. “The maximum fee would be increased to $90 and PERC granted authority to adjust the fee for inflation thereafter,” Cámara wrote.

Building on recent ‘union killer’ legislation

Ultimately, the measure would have, in practice, bolstered a major union reform bill (SB 256) approved by Florida lawmakers in 2023 that made it harder for local and state government unions to collect member dues, while simultaneously requiring more workers to pay dues in order for their union to remain certified.

In a state where paying union dues is voluntary, union density is dismally low, and many are struggling to make ends meet as it is, recruiting more dues-paying member can be a challenge. The 2023 law, notably exempting GOP-friendly police and firefighter unions, required at least 60 percent of workers in a bargaining unit to be dues-paying members, or else face the risk of decertification.

Unions that fail to reach that threshold are now either decertified (effectively dissolved) or forced to file a petition for an election to recertify. So far, dozens have done so, gathering signed cards of support from at least 30 percent of workers in the bargaining unit for a recertification election.

“Some of our largest affiliates have pledged they will not lose a bargaining unit, and they’re making good on that pledge,” said Rich Templin, political director for the Florida AFL-CIO, in an interview with me last spring. “They’re spending an incredible amount of time and energy and resources to make that happen.”

Others either didn’t adequately prepare for the new mandate, or for whatever reason, decided not to bother with pursuing recertification (union officials have generally refused to explain this to me on-the-record).

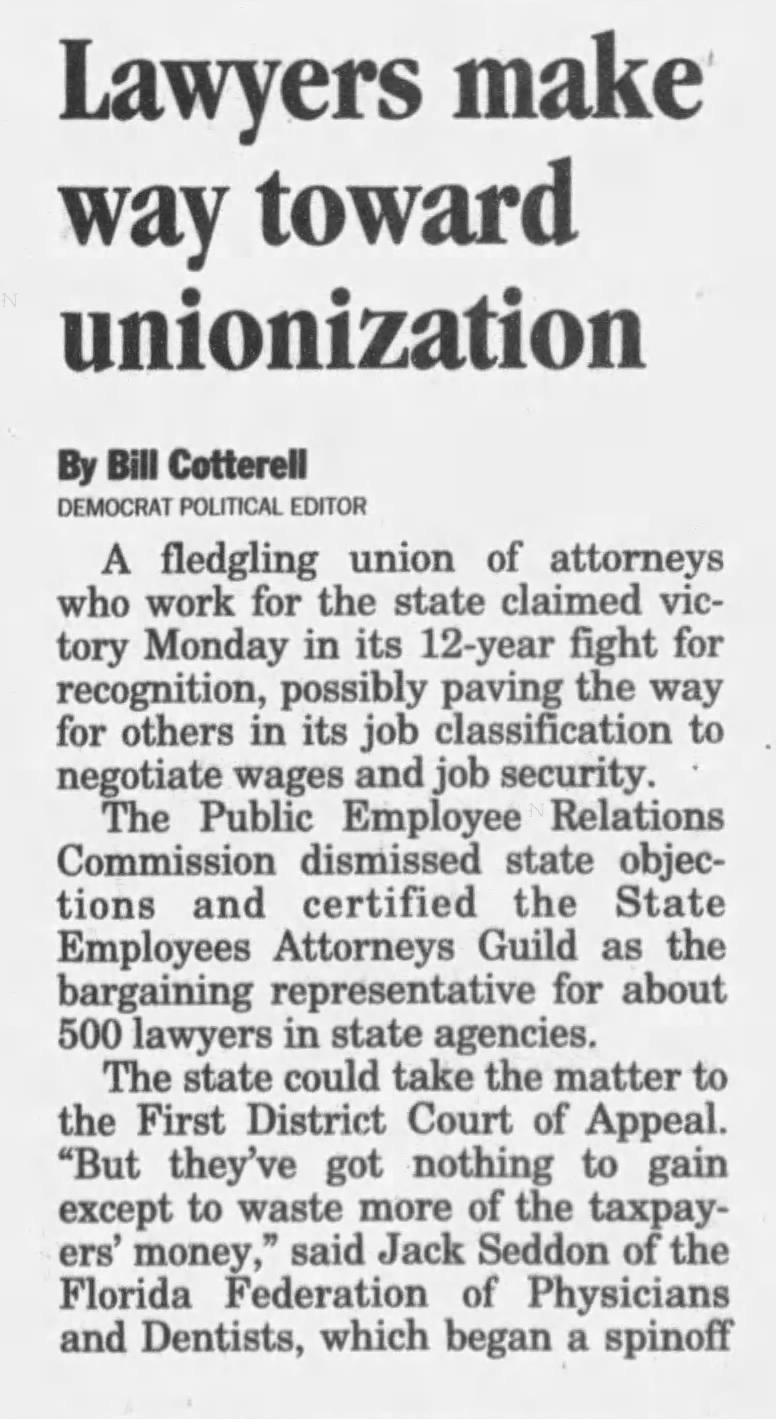

As a result of the law so far, more than 69,000 public employees in Florida have lost their union representation and, in effect, the rights they were previously guaranteed under their union contracts, from state-employed nurses, to utility workers in Lake Worth Beach (who are now re-organizing), to state-employed attorneys who fought for more than a decade to unionize back in the early aughts. Blue-collar employees at the University of South Florida, formerly represented by AFSCME, saw their jobs privatized.

More than 100 bargaining units have been decertified by the state so far. All but one were decertified not because workers voted to do so (that has only happened in one case), but because their union had a membership density of less than 60% and the union either didn’t petition for recertification, or failed to file paperwork renewing its registration with the state.

No surprise there

Templin, with the Florida AFL-CIO, told me in a recent interview that he wasn’t surprised by the governor’s involvement in the proposal this year, which would have made recertification much harder.

“We have known from the beginning that this legislation has never originated in Florida. It’s not addressing any actual problems in Florida, and as a matter of fact, it has victimized a lot of Florida workers — Republicans, Democrats and everybody,” Templin told me. “This is nothing that has ever been a priority of the legislature until the governor decided to run for president.”

DeSantis did see broad acquiescence from the Republican-controlled state legislature ahead of his wildly unsuccesful bid for U.S. President, and prioritized the anti-union law as part of his war on “woke” teachers unions. He has not enjoyed the same deference this year under different House and Senate leadership, however. Only the House version of this year’s anti-union bill (HB 1387) even received a single hearing, while the Senate version (SB 1776) was fully ignored.

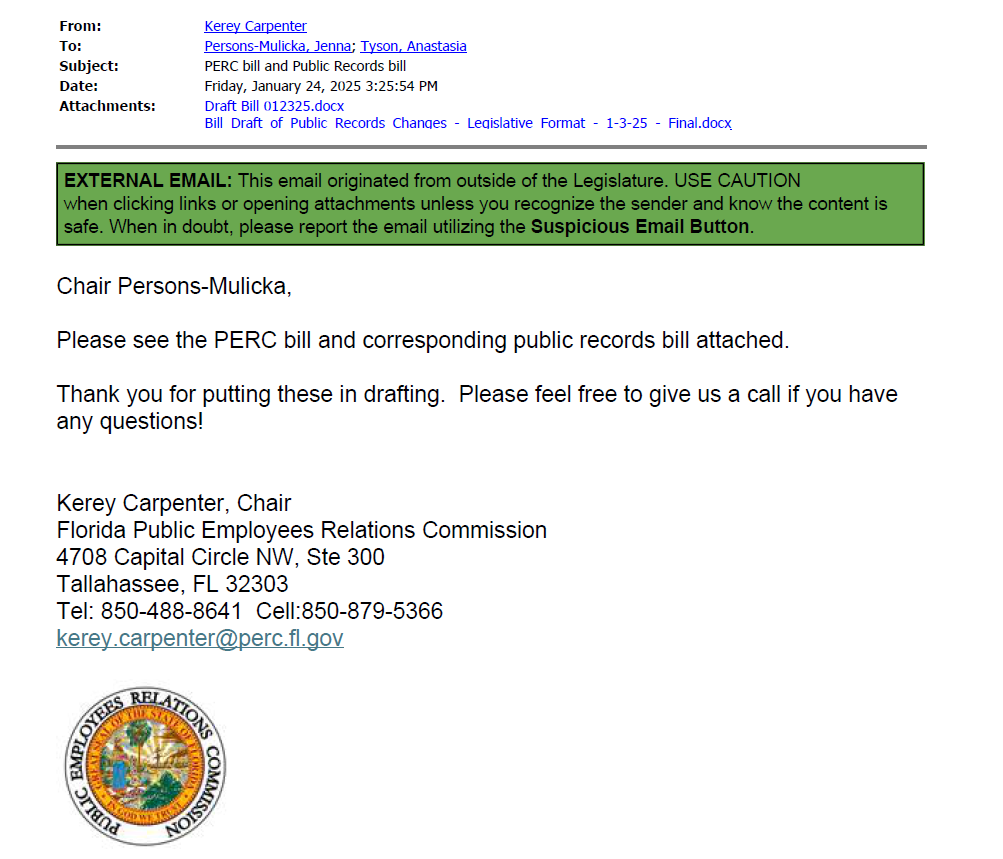

The Executive Office of the Governor, which is implicated in the email records and draft legislation I recently obtained, did not respond to a request for comment on their involvement in this proposal, nor its death. Nor did Kerey Carpenter, the chair of the Public Employees Relations Commission (PERC), who was also in communication about the bill with its Senate and House bill sponsors.

The Public Employees Relations Commission, a small state agency of about 30 employees, basically acts as the National Labor Relations Board for Florida’s public sector. It conducts union elections (including the new, massive wave of recertification attempts), investigates unfair labor practice allegations and the like. It’s also, notably, been unduly burdened by the 2023 union law, more than tripling its workload.

Metadata and comments on early versions of the anti-union proposal this year (which would have given Carpenter a salary boost) implicate Carpenter in the bill’s drafting, as well as a hearing officer and general counsel for her agency. The latter two offered feedback on technical issues (and suggested fixes) within the draft, while Carpenter appeared to coordinate communication efforts with the bill sponsors. She emailed draft legislation to them that they later filed for consideration by their respective chambers.

Carpenter, a Trump ally and former lawyer for a private equity investment company in Winter Park, was quietly appointed by DeSantis to lead the Commission last March. The leadership change wasn’t publicly announced, but came after a contentious rule-making process for the 2023 union law that left chaos and confusion in its wake.

“My guess is most people [unions] are going to get stronger, and get more dues payers, and we’re not going to have everyone on elections every year,” remarked former PERC chair Don Rubbotom during a Sept. 2023 rule-making workshop. “That’s my hope,” he added.

Andrew Spar, president of the statewide teachers’ union, previously told me he saw this year’s proposal as a response to unions’ broad success in recertifying, despite the challenges they’ve faced in doing so.

“We want our union, and we want this nonsense of making us jump through hoops to keep our union and to negotiate fair pay, fair benefits and fair working conditions to stop,” he told me in an interview for Orlando Weekly.

Despite hurdles imposed by the 2023 law, not a single FEA-affiliated union has been decertified yet, according to public election records. Members of dozens of other unions, meanwhile, are still waiting for their voices to be heard as PERC scrambles to schedule and conduct recertification elections.

A pattern of losses for DeSantis

This isn’t the first bill introduced during the 2025 state legislative session this year that appears to have come from Gov. DeSantis’ office and failed to pass. Last month, I reported for Orlando Weekly that a set of bills aiming to roll back the state’s child labor laws also came from the governor’s office.

DeSantis claimed publicly that Florida’s teenagers should be able to fill jobs vacated by immigrant and undocumented workers, as both the state and federal government work in lockstep to conduct the “largest deportation operation in American history.”

That proposal, like the anti-union proposal, died earlier this month, following the conclusion of most of state lawmakers’ policy work this session.

Florida’s 2025 legislative session officially kicked off in early March and was scheduled to end Friday, May 2. Because lawmakers didn’t reach an agreement on a state budget for the next fiscal year, however, they’ll be heading back to Tallahassee to hash things out. All but a select few bills pertaining to the budget that hadn’t been passed as of May 2 have officially been withdrawn and are presumed dead.

Among the deceased this year include efforts to strip temp workers of decades-old labor protections, gift employers a minimum wage loophole, and make it harder for Floridians to access the state’s meager unemployment benefits.